Our research: case studies

Looking at lung cancer without surgery

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer-related death. Giving patients the best possible treatment depends on understanding how far the disease has spread through the body at diagnosis.

The standard way to assess how far lung cancer had spread involved invasive surgery to count the number of chest lymph nodes that the cancer had spread to. This approach was not very sensitive and required the patient to undergo surgery.

Cambridge cancer researchers led the international NIHR Cambridge BRC and NIHR Health Technology Assessment ASTER trial. Using an alternative, non-surgical approach called endosonography (an endoscopy combined with ultrasound to obtain images of the internal organ), the procedure was found to be more accurate, a safer way to assess the spread of the lung cancer and also gave patients a much better quality of life.

Not only are the results to using endosonography more accurate, but is also much cheaper than a surgical procedure. As a result this new approach has replaced surgery as the front line test for lung cancer spread and over 100 centres now provide this service in the UK, cutting the rate of surgical lymph node staging in the UK from 3,020/year in 2010 to 1,854 in 2015.

Detecting cancer with a ‘pill on a string’

Some people who have long-term symptoms of heartburn or acid reflux develop a condition called Barrett’s oesophagus, areas of abnormally developing cells that may turn into cancer in a small number of people.

Early detection of this type of cancer requires a referral for an endoscopy, where a camera is fed through your mouth to your stomach, which can be uncomfortable for some people and is expensive for the health service.

However, researchers in Cambridge have come up with a new way to collect cells from the oesophagus to test for cancer, which is easier and less uncomfortable than an endoscopy and importantly can be performed in the GP surgery. The device, known as the cytosponge or ‘pill on a string’, only takes a few minutes to use and can be done outside of a hospital setting.

Patients are asked to swallow a small capsule (about the size of a multivitamin pill) which is attached to a string. When it gets to the stomach the capsule disintegrates and releases a small sponge. The sponge is then pulled back using the string, collecting cells as it comes up the oesophagus which can be sent off for testing. The team have also devised the laboratory test to make the testing as fast and accurate as possible.

The cytosponge is now in its third stage of trials at GP practices and results are expected within a year. Early tests have shown them to be effective at detecting Barrett’s oesophagus. If trials continue to show positive results, the device could provide more patients to be tested for the possibility that they have Barrett’s oesophagus.

This means testing can take place in the community, identifying those who have suspected Barrett’s oesophagus faster and reducing the number of those who require an endoscopy. The cytosponge could revolutionise testing and save the NHS money.

This research was supported and funded by the Medical Research Council, Cancer Research UK and the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

Find out the journey of the timeline from an idea to now a a new diagnostic tool to detect Barrett’s oesophagus.

New device could improve safety of routine testing for prostate cancer

Prostate cancer is the most common cancer in men in the UK, with around 1 in 8 men affected at some point in their life.

Clinicians currently diagnose patients using a technique called trans-rectal ultrasound, which is where a small ultrasound probe inserted into the back passage. However, this method can be unpleasant, and have side effects such as urinary infections or risk of sepsis.

Cambridge researchers have devised a new tool, called the CamProbe, that allows biopsies to be taken via the transperineal route (under the scrotum) where a sample of tissue is removed from the prostate for examination under a microscope. This can be done under local anaesthesia.

No infections were detected using this technique in the pilot studies, compared with the 5-12% using the standard method, and most trial participants preferred the CamProbe test.

Now with further funding, clinical trials are underway to test the device on larger numbers of patients. If the results are positive, it will substantially improve the safety of routine testing for prostate cancer, reduce the risk of sepsis and antibiotic resistance and potentially save the NHS millions every year.

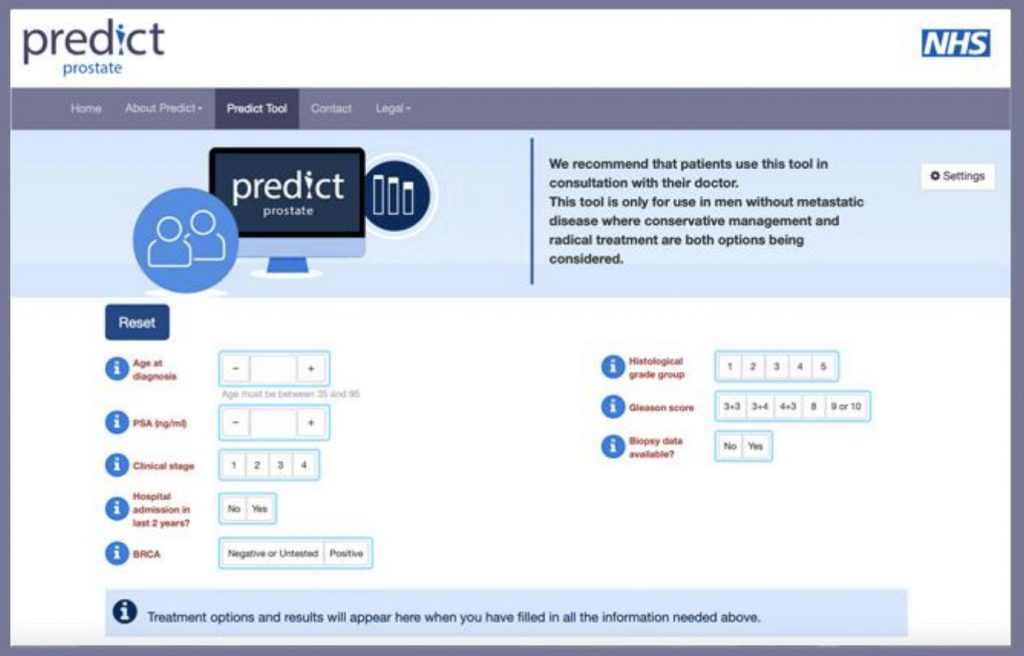

See also the PREDICT Prostate tool which gives patients a personalised prognosis of their disease

Evidence-based web tool aims to help inform treatment options in early prostate cancer

A new tool to predict an overall survival estimate for men following a prostate cancer diagnosis could help prevent unnecessary treatment and related side effects.

PREDICT Prostate has been developed by researchers at the University of Cambridge, led by Mr Vincent Gnanapragasam, University Lecturer and Honorary Consultant at Cambridge University Hospitals, and undertaken by Dr Thurtle, both of the Academic Urology Group in Cambridge, and in collaboration with Professor Paul Pharoah of the Department of Cancer Epidemiology.

The tool brings together the latest evidence and mathematical models to give a personalised prognosis, which aims to empower patients as they discuss treatment options with their consultant.

Mr Gnanapragasam said: “We believe this tool could significantly reduce the number of unnecessary – and potentially harmful – treatments that patients receive and save the NHS millions every year.”

Risk classification

Progression of prostate cancer is variable: in most cases, the disease progresses slowly and is not fatal. But in a significant number of men, the tumour will metastasise (spread to other organs in the body), threatening their health.

When a patient is diagnosed with prostate cancer, they are currently classified as low, intermediate or high risk, according to guidelines provided by NICE (the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

Depending on the patient’s risk group, clinicians will recommend either an ‘active monitoring’ approach or treatment. Treatment options include radiotherapy or surgery and can have potentially significant side-effects, including erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence.

But the risk classifications have been shown to be only 60-70% accurate – meaning many men may elect for treatment when it is not necessary.

What PREDICT Prostate does is take routinely available information including PSA test results, the cancer grade and stage, the proportion of biopsies with cancerous cells, and details about the patient including his age and other illnesses.

It then gives a 10-15 year survival estimate. Importantly, the tool also estimates how the patient’s chance of survival differs depending on whether he opts for monitoring or treatment, providing context of the likelihood of success of treatment and risk of side effects.

- In a randomised study of almost 200 prostate cancer specialists, those clinicians given access to the PREDICT tool were less likely to recommend treatment in good-prognosis cancers

- The tool is recommended for use only in consultation with a clinician. It is not suitable for men with very aggressive disease or who have evidence of disease spread at the time of diagnosis

- Every year, tens of thousands of men are diagnosed with prostate cancer. But what should they do? Listen to Vincent Gnanapragasam’s interview with the Naked Scientists

Cancer treatment could save millions

Women with early stage HER2-positive breast cancer typically take the drug trastuzumab for 12 months to reduce the likelihood of cancer returning. But results from a Cambridge study revealed that taking just six months of the drug delivered similar results.

The 2.6m PERSEPHONE trial, the largest of its kind and led by Professor Helena Earl, Cambridge researchers found 89.4 per cent of women taking six months treatment were free of breast cancer after four years compared with 89.8 per cent of patients taking treatment for twelve months.

In addition, just three per cent of women in the six month study had to stop taking the drug – also called Herceptin – because of heart problems compared with eight per cent of those who took it for 12 months.

The cost saving of a six month, rather than 12 month, treatment is estimated at £9,699 per patient and potential global savings could be in the millions annually.

The study and data from a parallel French trial will be used to explore whether there are subgroups of higher risk women for whom 12 months therapy would remain the most appropriate course.

This new evidence could change practice and will be considered by NICE and NHS England. Women currently taking the medication should not change their treatment without seeking the advice of their doctor.

Can a simple breath test detect cancer?

In a first-of-its kind, Cambridge researchers are working on a new trial to try and detect early stage cancer by testing people’s breath.

The PAN cancer trial will ask people to breathe into a mask for 10 minutes. Researchers will then try and detect molecules called ‘volatile organic compounds’ (VOCs) to see if they can signal cancer.

The clinical trial will involve both healthy volunteers, to better understand ‘normal’ VOC levels, and patients with a suspected cancer diagnosis to look at whether the level of VOCs in their breath is different. The trial, which began in January 2019, is currently recruiting patients with oesophageal and stomach cancers but will expand to include patients with liver, prostate, kidney, bladder and pancreatic cancers.

Professor Rebecca Fitzgerald, Chief investigator of the trial, and co-lead for the Early Detection Programme, Cancer Research UK Cambridge Centre, said: “We urgently need to develop new tools, like this breath test, which could help to detect and diagnose cancer earlier, giving patients the best chance of surviving their disease. Through this clinical trial we hope to find signatures in breath needed to detect cancers earlier – it’s the crucial next step in developing this technology. Owlstone Medical’s Breath Biopsy® technology is the first to test across multiple cancer types, potentially paving the way for a universal breath test.”

If the trial is successful, researchers hope they can identify cancer sooner, reduce the need for invasive testing and roll this simple test out to GP’s surgeries.

The Cancer Research UK Cambridge Centre is running the PAN Cancer trial for Early Detection of Cancer in Breath in collaboration with Owlstone Medical to test their Breath Biopsy® technology.

Watch the ITV News story

Cambridge GPs launch ‘pill on a string’ cancer check

A Cambridge device to spot early signs of cancer is being trialled for the first time to GP patients in the UK.

The cytosponge or ‘pill on a string’ has been designed to help detect the early stages of oesophageal cancer.

Developed by the University of Cambridge and supported by the NIHR Cambridge BRC and NIHR Cambridge Clinical Research Facility, the device is now being trialled with GP patients in a mobile unit, known as the Heartburn Sponge Test unit. After Cambridge it will move on to Essex and then Suffolk as the pilot aims at proving a wider benefit to the NHS.

The hope is this new, quick and potentially life-saving device will detect the early signs of oesophageal cancer and treatment can begin a lot sooner.

The cytosponge is a small pill with a thread attached that the patient swallows, which expands into a small sponge when it reaches the stomach.

It is quickly pulled back up the throat by a nurse, collecting cells from the oesophagus which will be sent for analysis.

The procedure takes around 10 minutes and can be performed in a GP surgery.

Because oesophageal cancer is often found late, it is usually fatal. Only 17% of people diagnosed with it live for a further five years or more after diagnosis.

It is hoped the cytosponge could one day become a test used by GP surgeries throughout the country to identify potential issues for people who are on long-term heartburn medication, or when someone has had heartburn or indigestion for three weeks or more.

This is an abridged version of the article first published on our website on 17 June 2021.

New study to test personalised breast cancer screening

A new international trial will investigate whether a personalised breast cancer screening can help detect the disease sooner.

MyPeBS trial is taking place in 6 European countries and plans to involve 85,000 volunteers aged between 50 and 70 who have never had breast cancer before.

Currently those between the ages of 50-70 are invited for a routine NHS breast cancer screening by having a mammogram every three years. However, not everyone has the same breast cancer risk, other factors such as genetics, hormones, family history and breast density can put some in a higher risk category.

The MyPeBS study randomly assigns trial volunteers to follow either the standard NHS screening schedule or a personalised screening schedule according to their risk of breast cancer.

Professor Fiona Gilbert, professor of radiology at University of Cambridge and imaging theme lead for the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre is leading the UK study. “This is an opportunity to take part in one of the largest studies so far into how we find early stage breast cancer. By taking a saliva sample and history from those selected on the trial, we can identify whether they are at higher or lower risk of developing breast cancer. Once we know this, we can tailor screening to their own personal needs.”

Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (CUH), the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust and Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) will be supporting the UK arm of the study and plans to recruit 10,000 volunteers which will last for 4 years. The Cambridge site will be supported by the NIHR Cambridge BRC.

For more information about the trail, go to: www.mypebs.eu

ITV News reported on the trial in October 2021 or read the full news article.

NICE prostate guidelines updated based on Cambridge research

A Cambridge developed model to risk-categorise prostate cancer was added to the NICE guidelines and adopted as standard practice in the NHS in 2021.

Patients with a raised blood level of Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) or other worrying symptoms have tests to determine any presence of cancer. If they are diagnosed with the disease, they were normally categorised in one of three groups, low, intermediate or high-risk, depending on the severity of the cancer, and start treatment.

However, research supported by the NIHR Cambridge BRC, demonstrated that some patients did not fit neatly into any of the categories and so did not require the same monitoring and treatments compared to others in the respective groups.

They developed a new risk model – the Cambridge Prognostic Groups (CPG), which re-categorised these groups into five categories.

After years of collecting detailed health information and testing, the team found having five categories was a better method to inform the best treatment choice and also likelihood of the disease responding to treatment.

NICE recognised all newly diagnosed men in the UK should be risk-categorised by the new five category model developed in the CPG’s criteria which will now improve care and tailor appropriate treatment to patients.