Our research: case studies

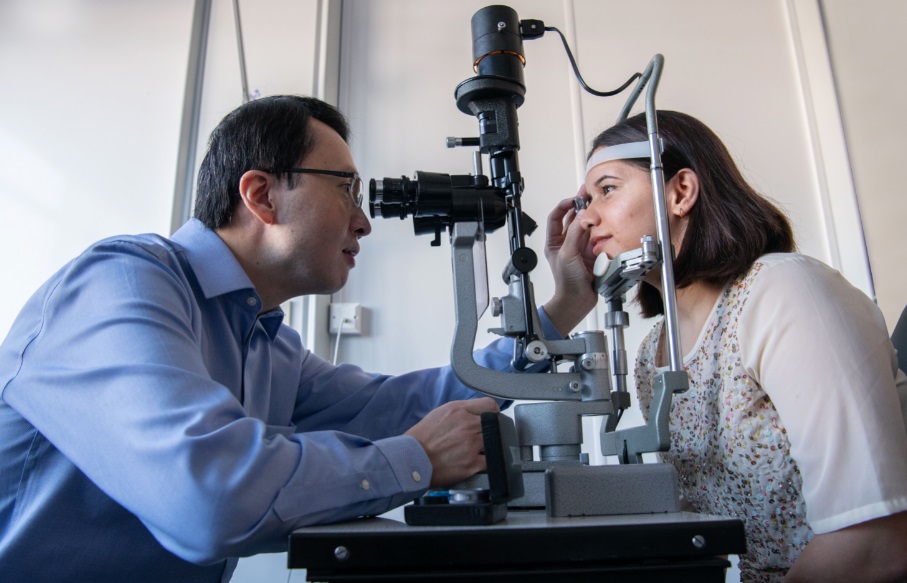

Gene therapy for inherited blindness

Leber hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON) is a rare inherited form of blindness that mainly affects younger men. It is usually caused by a spelling mistake (mutation) in the genetic code (DNA).

We used gene therapy to inject a working copy of the mutated code via injection into patients’ eyes, under local anaesthetic.

The treatment was well tolerated and around 80% of patients noticed an improvement in their vision.

This treatment is now being evaluated by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). We have also received funding from the NIHR to conduct another study to see if patients if this treatment benefits patients with LHON who have lost vision for longer than one year.

Brain repair in multiple sclerosis

Over 100,000 people in the UK have multiple sclerosis (MS). Licensed drugs can reduce the chance of having MS attacks but people with MS are still left with disability.

This is because after an attack the nerves have no insulating covering of myelin. Laboratory work in Cambridge showed that certain drugs can wake up stem cells in the brain to repair myeli.

We tested whether the anti-cancer drug bexarotene can repair myelin in people with MS.

We gave bexarotene or placebo to 50 people with MS for 6 months. At the beginning and the end of the study, these participants had a MRI scan of the brain and a “VEP” (Visual Evoked Potentials) test to see how quickly signals travel from the eye to the brain.

People on bexarotene had quicker “VEP” signals and, in some parts of the brain, improved MS scars seen on MRI scans, showing that myelin has been repaired. Unfortunately, the side effects of the drug were too severe to consider further development with bexarotene.

Improving the outcome from head injury

Head injury is the commonest cause of death in young adults. Outcomes differ greatly between patients, and there are significant challenges in determining the best type of treatment for a particular individual.

We are developing new therapies linked to novel monitoring and scanning tools to guide patient care. The discoveries are changing clinical guidelines, routine practice, clinical training and the public understanding of head injury.

Our advances have improved the management and health outcomes of patients with head injury, through changes to clinical guidelines. Impact has also occurred on training health care professionals (in the UK and globally), and in public policy, awareness and understanding.

Alemtuzumab in Multiple Sclerosis

Cambridge BRC researchers were the first to use alemtuzumab in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) patients. Alemtuzumab had been developed in the 1980s (as “Campath”) in Cambridge to treat cancers.

T and B white blood cells normally attack bacteria, but in patients with MS, these white blood cells attack the nerves in the brain and spinal cord. In trials done from 1991 to 2012, researchers found that alemtuzumab stopped the immune system from attacking these nerves. As a result, patients with multiple sclerosis did not get worse, and indeed often noticed an improvement in their disability; this has never been achieved before.

Alemtuzumab was licensed in Europe in 2013 and approved by NICE in 2014. It is now been licenced in over 50 countries, and administered to tens of thousands of people with multiple sclerosis.

Link between amino acid and a range of common diseases could help predict personal risk

Damage or disruption to mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) – the powerhouse of cells – can cause or influence many common diseases but is there a link between mtDNA variants and increased risk of disease?

A study involving researchers from the Wellcome Sanger Institute, the University of Cambridge and EMBL’s European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) indicates that yes, there is a link.

In this collaborative study, supported by the NIHR Cambridge BRC, researchers looked at mtDNA variants in two large-scale datasets, and found that higher levels of the amino acid N-formylmethionine (fMet) are associated with increased risk of a wide range of late-onset diseases including kidney disease and heart failure.

While further study is required, fMet seems to be a promising biomarker that could be used to better predict an individual’s risk of developing a wide range of common diseases and plan pre-emptive interventions.