Working to improve clinical knowledge and the way we care for people

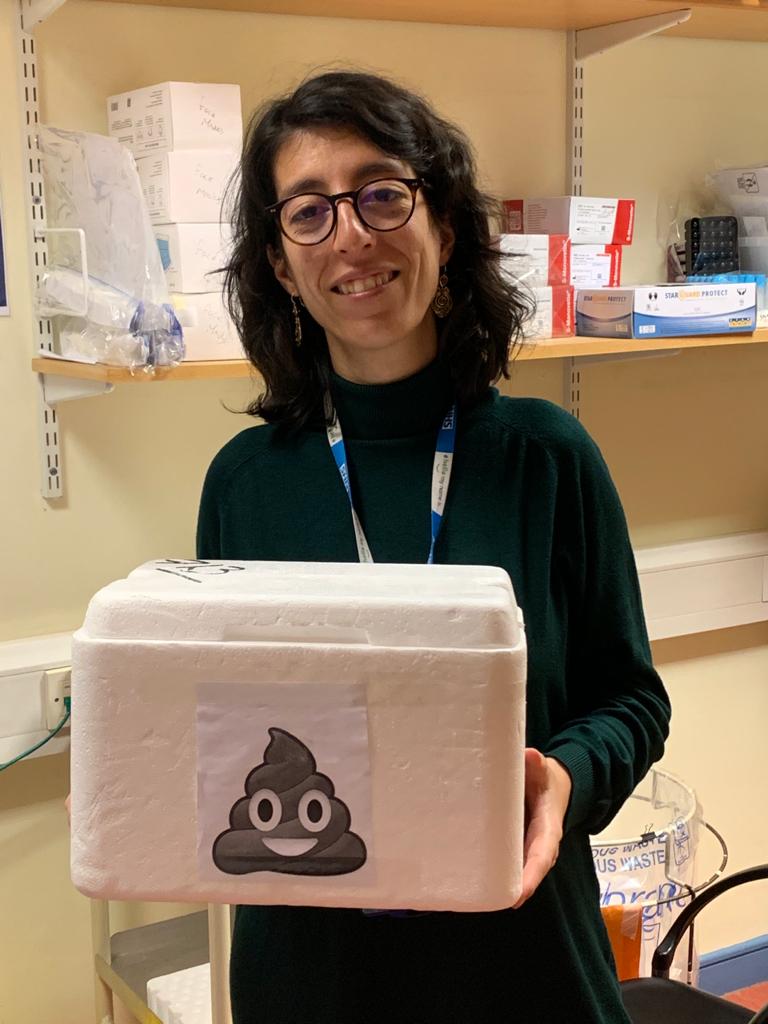

Marta Camacho (pictured, left, holding a stool box) is a research assistant supporting research into Parkinson’s Disease (PD).

Read more about her work – and the meaning of that stool box! – below.

What are you currently working on?

Our group is leading the PICNICS and CamPaiGN studies, which are observational studies tracking PD progress over time. We also look after the Cambridge Incident Cohort, composed of more than 600 individuals with PD, who are assessed every 18/24 months.

These studies have given us a lot of valuable data going back up to 18 years, and with this we identified several factors associated with different progression trajectories in PD. We are now working on a clinical trial for PD, which will start in March 2021.

Most of my responsibilities revolve around coordination of follow-up visits and data collection (including home visits for those who can no longer attend the research clinic). During our research visits we assess detailed clinical measures, cognitive tests and collect blood samples. I also manage the databases of these cohorts, doing quality control, running queries for our group’s researchers and for external collaborators/data consortiums.

Could you tell us more about your PhD and what you plan to do after you’ve completed it?

I am in my second year of a part-time PhD in Clinical Neurosciences. As a database manager I had the opportunity to analyse one of our cohorts and we found that early constipation may be associated with more rapid disease progression in Parkinson’s Disease (PD).

I would now like to test the theory that abnormal gut function in PD leads to changes in the bacterial constituents of the gut (the gut microbiota) and increased inflammation, which in turn activates the immune system and accelerates PD progression.

Since I plan to finish in 2024 it is difficult to have a determined idea of what to do next but currently I would very much like to do a post-doc and continue working in the field of my PhD.

What is your biggest achievement to date?

I have won a couple of competitive grants that I am particularly proud of but, at the risk of coming across as unsophisticated, I often feel that my biggest achievement for the last 2 years is making it through another day.

I am a research assistant, a part-time PhD student in Clinical Neurosciences, a mother to a wonderful 3 year-old and I have severe ocular rosacea (a chronic eye condition that makes some days painfully difficult to work at the computer). But I keep going. Some days it is through sheer determination and many long nights/weekends. Other days, I owe it to the flexibility and understanding of my group and supervisors. Many more I owe to the support of my partner who, among many other things, cooks during the week. Above all, I am thankful and proud of the people I choose to be surrounded by.

What is rewarding about your job?

Within my everyday tasks, there are three that give me particular joy:

- organizing data – there is something very soothing about having data beautifully structured in a spreadsheet;

- analysing data: having a question, thinking whether and how the data can answer it and going through the process of finding a result, thinking about it and discussing it with colleagues – I thoroughly enjoy this process; and, most importantly,

- meeting people, particularly patients and their families, being witness to their ordinary acts of kindness, bravery and altruism when faced with a neurodegenerative disease.

What challenges/ difficulties do you face as a researcher?

There are many challenges in research, the first one being securing funding and acknowledging how this impacts your projects in a variety of ways – from methodology, to project results to your work-life balance. After securing funding, time management is of crucial importance – implementation an ambitious project requires an enormous amount of administrative hours and depends on an incredible number of different people in different departments, from HR, to finance, to legal. My success is very much dependent on how well I coordinate these essential requirements.

What have you learnt since becoming a researcher?

My critical thinking has improved with my experience as a researcher and it is the one that I treasure most. As a researcher, I purposefully and willingly share my work with others to be scrutinized. I welcome that others point out where I missed an important link or how an interpretation of a given finding may be at fault. It’s a sharpening and humbling exercise that transcends my line of work and shapes how I read and deal with the world around me.

Why is your role important?

In a nutshell, my job is to make sure our research cohorts run smoothly so that we gather robust data with which we can understand PD progression better. Much of my work is invisible but I feel it offers me the position to contribute to something that will improve clinical knowledge and ultimately the way we care for people.

How did you get into research?

I did my masters in cognitive aging as part of my academic training in Coimbra University (Portugal) and it was very clear to me that I would like to do research but I first worked in a memory clinic so that I gained my specialty as a Clinical Neuropsychologist. I then joined Neuroscience Programme at the Champalimaud Foundation in Lisbon, as a neuropsychologist and research assistant. There, I had clinical work in the mornings and, in the afternoons, I collaborated in several research projects, including post-ingestive mechanisms of reward in obesity and taste sensitivity and reward in Parkinson’s Disease. I had always wanted to pursue a PhD so after a few years, I applied to Cambridge as a research assistant and got accepted into the Clinical Neuroscience PhD programme a year later.

With the knowledge and experience you have now, what advice would you give yourself 10 years ago?

Take a break – your sense of worth is not measured by your work load.

What opportunities are there for researchers in Cambridge?

Cambridge is a vibrant place to work and live. In terms of academic opportunities, I am frequently awed with the quantity and diversity of seminars, workhops, courses, journal clubs from different fields that I can attend. The heterogeneity of researchers that it attracts and whom you can meet and collaborate with feels unpararelled. Also, the college structure allowed me to be friends with science philosophers and physicists turned historians and I often feel richer and humbled by our diverse discussions. The city itself offers a great quality of life and it is a wonderful place to raise a family.

What makes Cambridge a great place to conduct research?

There are many factors that make the department of Clinical Neuroscience in Cambridge a great place to work and study. What struck me most was the extent to which individuals within and outside my own group are willing to collaborate and cooperate in our research projects. This attitude of giving someone your time, effort and knowledge so that they can improve their work and we can all achieve the highest level of research is something that I really appreciate and I am proud to be a part.

What advice would you give to someone thinking about pursuing a career in research?

Don’t do a PhD straight after your undergraduate studies. Be a research assistant in several labs, do clinical work or work in industry, just for a couple of years. During this period, consolidate techniques, sharpen your critical thinking, recognize weaknesses and strengths, learn what you would like to research one day, learn to manage expectations. Acquire knowledge and experience that will be crucial for you to have a mature PhD experience, in which not everything is new and overwhelming. I do not regret doing this. Sure, it can be awkward to be the only 30+ year old in a room with 23-year-old fellow PhD students but I would like to believe that my wrinkles are not the only thing that shines through.

Why do you think research is important?

Research is vital to create knowledge and tools that not only describe and improve the world around us but ultimately save lives. To me research offers something almost equally important, a human process through which we can try to understand the mechanisms and intricacies of any given subject. It is the most noble of human attempts.

What work have you been doing during the Covid-19 pandemic?

The first lockdown halted research visits with patients but I continued to work remotely on database queries, data analysis and writing papers. It was very difficult for all of us but as we work mainly with older adults it was important that we ensured their safety. Since then, we have been very busy trying to recuperate the backlog of follow-up visits by seeing as many patients as we possibly can in a safe manner while preparing for an exciting new clinical trial.