Brain training app improves users’ concentration, study shows

A new ‘brain training’ game designed by researchers at the University of Cambridge improves users’ concentration, according to new research published. The scientists behind the venture say this could provide a welcome antidote to the daily distractions that we face in a busy world.

In their book, The Distracted Mind: Ancient Brains in a High-Tech World, Adam Gazzaley and Larry D. Rosen point out that with the emergence of new technologies requiring rapid responses to emails and texts and working on multiple projects simultaneously, young people, including students, are having more problems with sustaining attention and frequently become distracted. This difficulty in focussing attention and concentrating is made worse by stress from a global environment that never sleeps and also frequent travel leading to jetlag and poor quality sleep.

“We’ve all experienced coming home from work feeling that we’ve been busy all day, but unsure what we actually did,” says Professor Barbara Sahakian from the Department of Psychiatry. “Most of us spend our time answering emails, looking at text messages, searching social media, trying to multitask. But instead of getting a lot done, we sometimes struggle to complete even a single task and fail to achieve our goal for the day. Then we go home, and even there we find it difficult to ‘switch off’ and read a book or watch TV without picking up our smartphones. For complex tasks we need to get in the ‘flow’ and stay focused.”

In recent years, as smartphones have become ubiquitous, there has been a growth in the number of so-called ‘brain training’ apps that claim to improve cognitive skills such as memory, numerical skills and concentration.

Now, a team from the Behavioural and Clinical Neuroscience Institute at the University of Cambridge, has developed and tested ‘Decoder’, a new game that is aimed at helping users improve their attention and concentration. The game is based on the team’s own research and has been evaluated scientifically.

In a study published in the journal Frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience Professor Sahakian and colleague Dr George Savulich have demonstrated that playing Decoder on an iPad for eight hours over one month improves attention and concentration. This form of attention activates a frontal-parietal network in the brain.

In their study, the researchers divided 75 healthy young adults into three groups: one group received Decoder, one control group played Bingo for the same amount of time and a second control  group received no game. Participants in the first two groups were invited to attend eight one-hour sessions over the course of a month during which they played either Decoder or Bingo under supervision.

group received no game. Participants in the first two groups were invited to attend eight one-hour sessions over the course of a month during which they played either Decoder or Bingo under supervision.

All 75 participants were tested at the start of the trial and then after four weeks using the CANTAB Rapid Visual Information Processing test (RVP). CANTAB RVP has been demonstrated in previously published studies to be a highly sensitive test of attention/concentration.

During the test, participants are asked to detect sequences of digits (e.g. 2-4-6, 3-5-7, 4-6-8). A white box appears in the middle of screen, of which digits from 2 to 9 appear in a pseudo-random order, at a rate of 100 digits per minute. Participants are instructed to press a button every time they detect a sequence. The duration of the test is approximately five minutes.

Results from the study showed a significant difference in attention as measured by the RVP. Those who played Decoder were better than those who played Bingo and those who played no game. The difference in performance was significant and meaningful as it was comparable to those effects seen using stimulants, such as methylphenidate, or nicotine. The former, also known as Ritalin, is a common treatment for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD).

To ensure that Decoder improved focussed attention and concentration without impairing the ability to shift attention, the researchers also tested participants’ ability on the Trail Making Test. Decoder performance also improved on this commonly used neuropsychological test of attentional shifting. During this test, participants have to first attend to numbers and then shift their attention to letters and then shift back to numbers. Additionally, participants enjoyed playing the game, and motivation remained high throughout the 8 hours of gameplay.

Professor Sahakian commented: “Many people tell me that they have trouble focussing their attention. Decoder should help them improve their ability to do this. In addition to healthy people, we hope that the game will be beneficial for patients who have impairments in attention, including those with ADHD or traumatic brain injury. We plan to start a study with traumatic brain injury patients this year.”

Dr Savulich added: “Many brain training apps on the market are not supported by rigorous scientific evidence. Our evidence-based game is developed interactively and the games developer, Tom Piercy, ensures that it is engaging and fun to play. The level of difficulty is matched to the individual player and participants enjoy the challenge of the cognitive training.”

The game has now been licensed through Cambridge Enterprise, the technology transfer arm of the University of Cambridge, to app developer Peak, who specialise in evidence-based ‘brain training’ apps. This will allow Decoder to become accessible to the public. Peak has developed a version for Apple devices and is releasing the game today as part of the Peak Brain Training app. Peak Brain Training is available from the App Store for free and Decoder will be available to both free and pro users as part of their daily workout. The company plans to make a version available for Android devices later this year.

“Peak’s version of Decoder is even more challenging than our original test game, so it will allow players to continue to gain even larger benefits in performance over time,” says Professor Sahakian. “By licensing our game, we hope it can reach a wide audience who are able to benefit by improving their attention.”

Xavier Louis, CEO of Peak, adds: “At Peak we believe in an evidenced-based approach to brain training. This is our second collaboration with Professor Sahakian and her work over the years shows that playing games can bring significant benefits to brains. We are pleased to be able to bring Decoder to the Peak community, to help people overcome their attention problems.”

The research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Written by the University of Cambridge

Clinical trial launches to develop breath test for multiple cancers

Researchers have launched a clinical trial to develop a breath test, analysing molecules that could indicate the presence of cancer at an early stage. This is the first test of its kind to investigate multiple cancer types.

A cancer breath test has huge potential to provide a non-invasive look into what’s happening in the body and could help to find cancer early, when treatment is more likely to be effective.

The Cancer Research UK Cambridge Centre is running the PAN Cancer trial for Early Detection of Cancer in Breath* in collaboration with Owlstone Medical** to test their Breath Biopsy® technology.

Breath samples from people will be collected in the clinical trial to see if odorous molecules called volatile organic compounds (VOCs) can be detected.

Professor Rebecca Fitzgerald

Professor Rebecca Fitzgerald, lead trial investigator at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Centre, said: “We urgently need to develop new tools, like this breath test, which could help to detect and diagnose cancer earlier, giving patients the best chance of surviving their disease.

“Through this clinical trial we hope to find signatures in breath needed to detect cancers earlier – it’s the crucial next step in developing this technology. Owlstone Medical’s Breath Biopsy® technology is the first to test across multiple cancer types, potentially paving the way for a universal breath test.”

When cells carry out biochemical reactions as part of their metabolism they produce a range of VOCs. If their metabolism becomes altered, such as in cancer and various other conditions, cells can release a different pattern of VOCs. The researchers aim to identify these patterns using Owlstone Medical’s Breath Biopsy® technology.

The researchers in the trial will collect samples from 1,500 people, including healthy people as trial controls, to analyse VOCs in the breath to see if they can detect signals of different cancer types. The clinical trial will start with patients with suspected oesophageal and stomach cancers and then expand to prostate, kidney, bladder, liver and pancreatic cancers in the coming months.

The trial is recruiting patients to Addenbrooke’s Hospital in Cambridge who have been referred from their GP with these specific types of suspected cancer – they will be given the breath test prior to other diagnostic tests. Patients will breathe into the test for 10 minutes to collect a sample, which will then be processed in Owlstone Medical’s Breath Biopsy laboratory in Cambridge, UK.

By looking across cancer types, this trial will help unpick if cancer signals are similar or different, and how early it’s possible to pick these signals up. Some people will go on to be diagnosed with cancer, and their samples will be compared to those who don’t develop the disease.

If the technology proves to accurately identify cancer, the team hope that breath biopsy could in future be used in GP practices to determine whether to refer patients for further diagnostic tests.

Billy Boyle, co-founder and CEO at Owlstone Medical, said: “There is increasing potential for breath-based tests to aid diagnosis, sitting alongside blood and urine tests in an effort to help doctors detect and treat disease. The concept of providing a whole-body snapshot in a completely non-invasive way is very powerful and could reduce harm by sparing patients from more invasive tests that they don’t need.

“Our technology has proven to be extremely effective at detecting VOCs in the breath, and we are proud to be working with Cancer Research UK as we look to apply it towards the incredibly important area of detecting early-stage disease in a range of cancers in patients.”

Almost half of cancers are diagnosed at a late stage in England***. This highlights the importance of early detection, particularly for diseases like oesophageal cancer where only 12% of oesophageal cancer patients survive their disease for 10 years or more.

Rebecca Coldrick, 54 from Cambridge, was diagnosed in her early 30s with Barrett’s oesophagus, a condition where the cells lining the oesophagus are abnormal – often caused by acid reflux. Out of 100 people with Barrett’s oesophagus in the UK, up to 13 could go on to develop oesophageal adenocarcinoma****.

Rebecca Coldrick said: “About 20 years ago I developed acid reflux, and I began to live on Gaviscon and other indigestion remedies. I went to the doctors and shortly after I was diagnosed with Barrett’s. Every two years I have an endoscopy to monitor my condition.”

Monitoring patients to find those at high risk of developing a cancer, like oesophageal, is very intrusive for patients, who may not even develop the disease. Rebecca Coldrick decided to take part in the PAN Cancer trial for Early Detection of Cancer in Breath. A non-invasive test using this technology could help to further differentiate those likely to develop oesophageal cancer from those less likely to develop the disease.

She added: “I was very happy to take part in the trial and I want to help with research however I can. Initially, I thought I might feel a bit claustrophobic wearing the mask, but I didn’t at all. I found watching the display on the computer during the test interesting and soon we were done, without any discomfort.

“I think the more research done to monitor conditions like mine and the kinder the detection tests developed, the better.”

Dr David Crosby, head of early detection research at Cancer Research UK, said: “Technologies such as this breath test have the potential to revolutionise the way we detect and diagnose cancer in the future.

“Early detection research has faced an historic lack of funding and industry interest, and this work is a shining example of Cancer Research UK’s commitment to reverse that trend and drive vital progress in shifting cancer diagnosis towards earlier stages.”

Recognising the importance of early detection in improving cancer survival, Cancer Research UK has made research into this area one of its top priorities and will invest more than £20 million a year in early detection research by 2019.

Further information:

While Owlstone will be funding the trial directly, none of this would be possible without the support and infrastructure provided by Cancer Research UK. The PAN Cancer trial is being conducted in collaboration with a team of leading cancer researchers at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Centre, the University of Cambridge and Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The Chief Investigator is Professor Rebecca Fitzgerald, who is co-lead of the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Centre Early Detection Programme, Professor of Cancer Prevention at the MRC Cancer Unit, and an Honorary Consultant in Gastroenterology and General Medicine at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge and is supported by the NIHR.

Written by CRUK and Owlstone. Image provided courtesy of Owlstone Medical Ltd

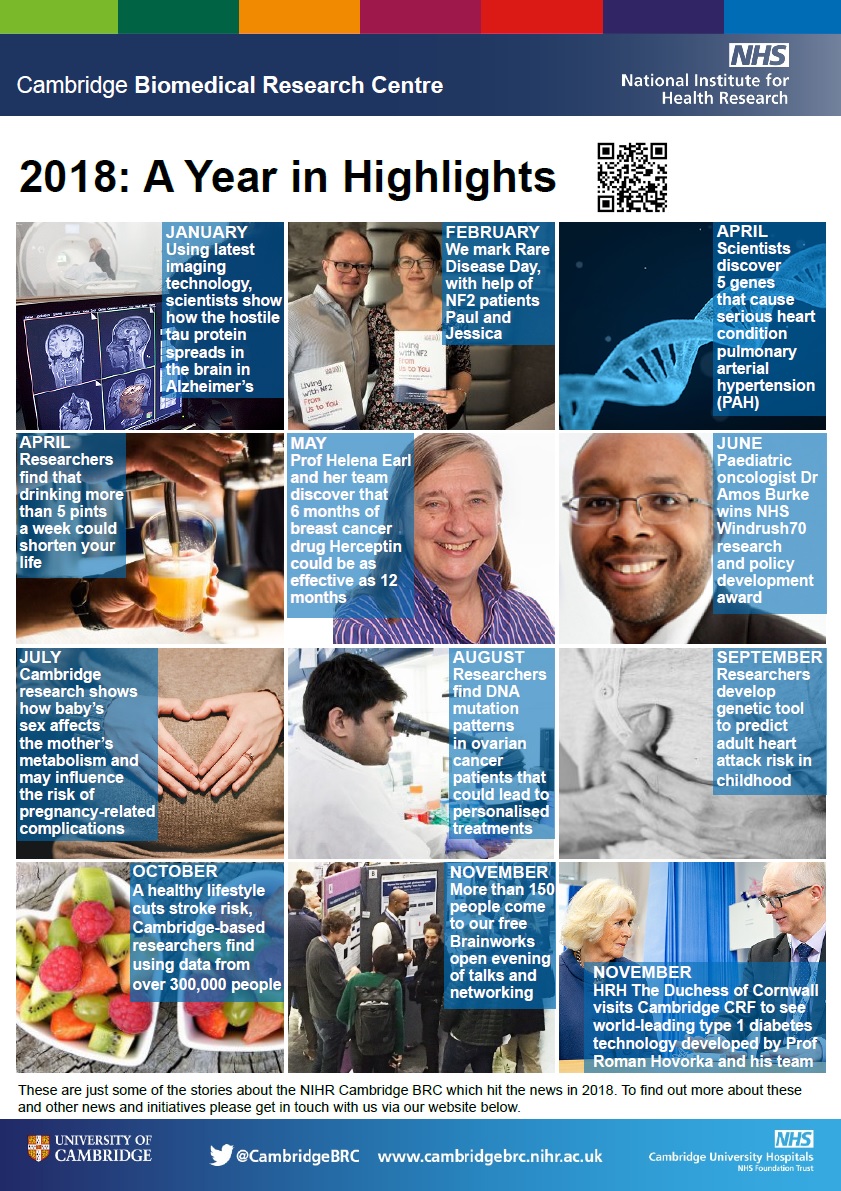

A year in highlights

As 2018 draws to a close, we reflect on the busy year our researchers have had.

We have looked back and picked some of our important research stories from the year.

Click on the picture below to take you to some of our featured highlights.

HRH The Duchess Of Cornwall visits Cambridge CRF to see the artificial pancreas

Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall visited Addenbrooke’s Hospital on Tuesday 27 November to see the world-leading type 1 diabetes technology being developed there by Professor Roman Hovorka of the University of Cambridge.

The Duchess, who is President of the type 1 diabetes charity JDRF, was greeted at the Cambridge Clinical Research Centre (CCRC) by the Deputy Lieutenant of Cambridgeshire, Penelope Walkinshaw.

Her Royal Highness The Duchess of Cornwall and Professor Roman Hovorka

Karen Addington, Chief Executive of JDRF in the UK and Caroline Saunders, Director of Clinical Operations at the CCRC then accompanied Her Royal Highness to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Cambridge Clinical Research Facility to meet researchers Professor Roman Hovorka and Dr Conor Farrington.

JDRF drives research into new treatments that present tremendous opportunities to deliver enhanced health and wellbeing for people with type 1 diabetes.

Her Royal Highness has been President of JDRF in the UK for over five years and during this time has met many individuals and families affected by type 1 diabetes, as well as the scientists and researchers working to cure, treat and prevent the condition, supported by JDRF. She previously met Professor Hovorka when she visited Addenbrooke’s in 2012.

Professor Hovorka has been developing the artificial pancreas since 2006 with research funded by JDRF and NIHR at the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

The artificial pancreas is now in advanced human trials after being found to be better at helping people with type 1 diabetes manage their blood glucose levels by keeping them in range 65% of time, compared with 54% of the time without the technology. A prototype of the artificial pancreas is currently being trialled across six centres in the UK including the NIHR Cambridge Clinical Research Facility.

Her Royal Highness was also introduced to Rob Hewlett, an adult patient who has been helping with the artificial pancreas trials and Janet Allen, a clinical research nurse.

In attendance at the event was Sky News presenter and JDRF supporter, Stephen Dixon who was diagnosed with type 1 when he was 17. He was accompanied by JDRF Youth Ambassadors George Dove and Amy Wilton who also met Her Royal Highness when she visited Addenbrooke’s in February 2012.

The Duchess was handed a posy of flowers by George Vinnicombe aged seven, and his sister Ava, aged five. George was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes when he was six months old and spent a considerable time in intensive care.

Written by JDRF

Kidney dialysis patients needed for Cambridge research study

Cambridge researchers, with support from NHS Blood and Transplant Clinical Trials Unit and funded by the National Institute for Health Research, are asking patients with failing kidneys who opt to have a fistula created in their arm for dialysis to take part in a new research trial.

In what is believed to be the first of its kind, the SONAR trial will use non-invasive ultrasound scans to monitor the maturation of arteriovenous fistulae (AVF) in patients.

Up to half of all AVF fail within the first year and researchers want to know why this happens and if it can be prevented.

Transplant surgeon Gavin Pettigrew, who is leading the nationwide study, said: “Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a major burden on the NHS and affects around 1.8 million people in England alone.

Gavin Pettigrew

“Of these, a small minority – 57,000 in 2016 – will progress to ‘end-stage kidney disease’, where regular dialysis treatment or kidney transplantation is needed.

“Haemodialysis, where you are hooked up to a machine which flushes the excess fluid and toxins from your blood, is the most common form of dialysis.

“This is performed either through a major vein or through an AVF, which is created by joining a small artery to a vein, usually in the patient’s arm.

“This is less risky than inserting lines into bigger veins and is more popular among patients.

High failure rate

“The downside is that, despite successful surgery, nearly half of all procedures to create AVF fail in the first year.

“This isn’t harmful to the patient, but we don’t know why this happens or if we can prevent it.”

The SONAR study aims to address both these questions over two stages.

In stage one, researchers will scan 347 patients immediately after their AVF surgery, using non-invasive ultrasound to see if they can spot early problems.

Mr Pettigrew said: “We’ll observe patients for 10 weeks following their surgery, during which they’ll have four ultrasound scans.

“The results from this study will improve our knowledge of how fistulae grow and whether ultrasound can predict problems at an early stage.”

In stage two, more than 1,200 patients will be selected to see if surgical interventions can prevent AVF failure.

Patient involvement

Early on Mr Pettigrew invited CKD patient Andrew Norton to join the SONAR steering committee as a lay member.

Andrew Norton

Andrew said: “My fistula was created two years ago and there were no problems, but I know many people whose fistulae have failed and they’ve had to have the operation again.

“SONAR could shed some light on why this happens, which is why I want to promote the potential benefits of taking part to new patients.”

As the patient representative, Andrew backed the group’s decision to apply to the Addenbrooke’s Kidney Patient Association (AKPA) for funding to cover travel costs for SONAR participants.

He said: “SONAR means an extra four visits for patients and for some this could be too expensive, even if they wanted to take part.

“Now that there is funding for this, it may encourage more patients who are about to have a fistula to join SONAR.”

Mr Pettigrew said: “Our end goal is to show that screening is beneficial, by targeting patients whose AVF is not working sooner and reduce the number of fistulae which fail.

“This will save money and time for the NHS and also improve care for the patients who are undergoing this procedure.

“The study will run over the next 15 months and we’re asking all patients with a new AVF, or who are just about to have one, to come forward and take part.”

More information:

- To find out more about SONAR visit their website: http://www.sonartrial.org.uk/

- SONAR is also on Twitter: @SONAR_TRIAL

- The SONAR trial is funded by a £1.8m grant from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme. Funding from the Addenbrooke’s Kidney Patients Association (AKPA) will help fund local patients’ travel expenses.

- SONAR is the acronym for Surveillance Of arterioveNous fistulAe using ultRasound study, sponsored by Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Cambridge. SONAR is managed by the Clinical Trials Unit at NHS Blood and Transplant.

- ‘It’s my lifeline’, read Andrew’s story about being involved in research

A healthy lifestyle cuts stroke risk, irrespective of genetic risk

People at high genetic risk of stroke can still reduce their chance of having a stroke by sticking to a healthy lifestyle, in particular stopping smoking and not being overweight, finds a study in The BMJ today.

Stroke is a complex disease caused by both genetic and environmental factors, including diet and lifestyle. But could adhering to a healthy lifestyle offset the effect of genetics on stroke risk?

An international team led by researchers at the University of Cambridge decided to find out by investigating whether a genetic risk score for stroke is associated with actual (“incident”) stroke in a large population of British adults.

They developed a genetic risk score based on 90 gene variants known to be associated with stroke from 306,473 white men and women in the UK Biobank – a database of biological information from half a million British adults.

Participants were aged between 40 and 73 years and had no history of stroke or heart attack. Adherence to a healthy lifestyle was based on four factors: non-smoker, diet rich in fruit, vegetables and fish, not overweight or obese (body mass index less than 30), and regular physical exercise.

Hospital and death records were then used to identify stroke events over an average follow-up of seven years.

Across all categories of genetic risk and lifestyle, the risk of stroke was higher in men than women.

Risk of stroke was 35% higher among those at high genetic risk compared with those at low genetic risk, irrespective of lifestyle.

However, an unfavourable lifestyle was associated with a 66% increased risk of stroke compared with a favourable lifestyle, and this increased risk was present within any genetic risk category.

A high genetic risk combined with an unfavourable lifestyle profile was associated with a more than twofold increased risk of stroke compared with a low genetic risk and a favourable lifestyle.

These findings highlight the benefit for entire populations of adhering to a healthy lifestyle, independent of genetic risk, say the researchers. Among the lifestyle factors, the most significant associations were seen for smoking and being overweight or obese.

This is an observational study, so no firm conclusions can be drawn about cause and effect, and the researchers acknowledge several limitations, such as the narrow range of lifestyle factors, and that the results may not apply more generally because the study was restricted to people of European descent.

However, the large sample size enabled study of the combination of genetic risk and lifestyle in detail. As such, the researchers conclude that their findings highlight the potential of lifestyle interventions to reduce risk of stroke across entire populations, even in those at high genetic risk of stroke.

Professor Hugh Markus from the Department of Clinical Neurosciences at University of Cambridge says: “This drives home just how important a healthy lifestyle is for all of us, even those without an obvious genetic predisposition. Some people are at an added disadvantage if ‘bad’ genes put them at a higher risk of stroke, but even so they can still benefit from not smoking and from having a healthy diet.”

The research was funded by the British Heart Foundation and the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Written by the University of Cambridge, Adapted from a press release by The BMJ.

Brain training app helps reduce OCD symptoms, study finds

A ‘brain training’ app could help people who suffer from obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) manage their symptoms, which may typically include excessive handwashing and contamination fears.

In a study published in the journal Scientific Reports, Baland Jalal and Professor Barbara Sahakian from the Department of Psychiatry, show how just one week of training can lead to significant improvements.

One of the most common types of OCD, affecting up to 46% of OCD patients, is characterised by severe contamination fears and excessive washing behaviour. Excessive washing can be harmful as sometimes OCD patients use spirits, surface cleansers or even bleach to clean their hands. The behaviours can have a serious impact on people’s lives, their mental health, their relationships and their ability to hold down jobs.

This repetitive and compulsive behaviour is also associated with ‘cognitive rigidity’ – in other words, an inability to adapt to new situations or new rules. Breaking out of compulsive habits, such as  handwashing, requires cognitive flexibility so that the OCD patient can switch to new activities instead.

handwashing, requires cognitive flexibility so that the OCD patient can switch to new activities instead.

OCD is treated using a combination of medication such as Prozac and a form of cognitive behavioural therapy (‘talking therapy’) termed ‘exposure and response prevention’. This latter therapy often involves instructing OCD patients to touch contaminated surfaces, such as a toilet, but to refrain from then washing their hands.

These treatments are not particularly effective, however – as many as 40% of patients fail to show a good response to either treatment. This may be in part because often people with OCD have suffered for years prior to receiving a diagnosis and treatment. Another difficulty is that patients may fail to attend exposure and response prevention therapy as they find it too stressful to undertake.

For these reasons, Cambridge researchers developed a new treatment to help people with contamination fears and excessive washing. The intervention, which can be delivered through a smartphone app, involves patients watching videos of themselves washing their hands or touching fake contaminated surfaces.

Ninety-three healthy people who had indicated strong contamination fears as measured by high scores on the ‘Padua Inventory Contamination Fear Subscale’ participated in the study. The researchers used healthy volunteers rather than OCD patients in their study to ensure that the intervention did not potentially worsen symptoms.

The participants were divided into three groups: the first group watched videos on their smartphones of themselves washing their hands; the second group watched similar videos but of themselves touching fake contaminated surfaces; and the third, control group watched themselves making neutral hand movements on their smartphones.

After only one week of viewing their brief 30 second videos four times a day, participants from both of the first two groups – that is, those who had watched the hand washing video and those with the exposure and response prevention video – improved in terms of reductions in OCD symptoms and showed greater cognitive flexibility compared with the neutral control group. On average, participants in the first two groups saw their Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (YBOCS) scores improve by around 21%. YBOCS scores are the most widely used clinical assessments for assessing the severity of OCD.

Importantly, completion rates for the study were excellent – all participants completed the one-week intervention, with participants viewing their video an average (mean) of 25 out of 28 times.

Mr Jalal said: “Participants told us that the smartphone washing app allowed them to easily engage in their daily activities. For example, one participant said ‘if I am commuting on the bus and touch something contaminated and can’t wash my hands for the next two hours, the app would be a sufficient substitute’.”

Professor Sahakian said: “This technology will allow people to gain help at any time within the environment where they live or work, rather than having to wait for appointments. The use of smartphone videos allows the treatment to be personalised to the individual.

“These results while very exciting and encouraging, require further research, examining the use of these smartphone interventions in people with a diagnosis of OCD.”

The smartphone app is not currently available for public use. Further research is required before the researchers can show conclusively that it is effective at helping patients with OCD.

The research was funded by the Wellcome Trust, NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, the Medical Research Council and the Wallitt Foundation.

Written by the University of Cambridge

Many cases of dementia may arise from non-inherited DNA ‘spelling mistakes’

Only a small proportion of cases of dementia are thought to be inherited – the cause of the vast majority is unknown. Now, in a study published today in the journal Nature Communications, a team of scientists led by researchers at the University of Cambridge believe they may have found an explanation: spontaneous errors in our DNA that arise as cells divide and reproduce.

The findings suggest that for many people with neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease, the roots of their condition will trace back to their time as an embryo developing in the womb.

In common neurodegenerative diseases, toxic proteins build up in the brain, destroying brain cells and damaging brain regions, leading to symptoms including personality changes, memory loss and loss of control. Only around one in twenty patients has a family history, where genetic variants inherited from one or both parents contributes to disease risk. The cause of the majority of cases – which are thought to affect as many as one in ten people in the developed world – has remained a mystery.

A team of researchers led by Professor Patrick Chinnery from the Medical Research Council (MRC) Mitochondrial Biology Unit and the Department of Clinical Neurosciences at the University of Cambridge hypothesised that clusters of brain cells containing spontaneous genetic errors could lead to the production of misfolded proteins with the potential to spread throughout the brain, eventually leading to neurodegenerative disease.

“As the global population ages, we’re seeing increasing numbers of people affected by diseases such as Alzheimer’s, yet we still don’t understand enough about the majority of these cases,” says  Professor Chinnery. “Why do some people get these diseases while others don’t? We know genetics plays a part, but why do people with no family history develop the disease?”

Professor Chinnery. “Why do some people get these diseases while others don’t? We know genetics plays a part, but why do people with no family history develop the disease?”

To test their hypothesis, the researchers examined 173 tissue samples from the Newcastle Brain Tissue Resource, part of the MRC’s UK Brain Banks Network. The samples came from 54 individual brains: 14 healthy individuals, 20 patients with Alzheimer’s and 20 patients with Lewy body dementia, a common type of dementia estimated to affect more than 100,000 people in the UK.

The team used a new technique that allowed them to sequence 102 genes in the brain cells over 5,000 times. These included genes known to cause or predispose to common neurodegenerative diseases. They found ‘somatic mutations’ (spontaneous, rather than inherited, errors in DNA) in 27 out of the 54 brains, including both healthy and diseased brains.

Together, these findings suggest that the mutations would have arisen during the developmental phase – when the brain is still growing and changing – and the embryo is growing in the womb.

Combining their results with mathematical modelling, their findings suggest that ‘islands’ of brain cells containing these potentially important mutations are likely to be common in the general population.

“These spelling errors arise in our DNA as cells divide, and could explain why so many people develop diseases such as dementia when the individual has no family history,” says Professor Chinnery. “These mutations likely form when our brain develops before birth – in other words, they are sat there waiting to cause problems when we are older.”

“Our discovery may also explain why no two cases of Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s are the same. Errors in the DNA in different patterns of brain cells may manifest as subtly different symptoms.”

Professor Chinnery says that further research is needed to confirm whether the mutations are more common in patients with dementia. While it is too early to say whether this research will aid diagnosis or treatment this endorses the approach of pharmaceutical companies who are trying to develop new treatments for rare genetic forms of neurodegenerative diseases.

“The question is: how relevant are these treatments going to be for the ‘common-or-garden’ variety without a family history? Our data suggests the same genetic mechanisms could be responsible in non-inherited forms of these diseases, so these patients may benefit from the treatments being developed for the rare genetic forms.”

The research was funded by Wellcome, the Evelyn Trust, Medical Research Council, and the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre.

Written by University of Cambridge

Genetic tool to predict adult heart attack risk in childhood

People at high risk of a heart attack in adulthood could be spotted much earlier in life with a one-off DNA test, according to new research part-funded by the British Heart Foundation and supported by the NIHR Cambridge BRC.

An international team led by researchers from the University of Leicester, University of Cambridge and the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute in Australia used UK Biobank data to develop and test a powerful scoring system, called a Genomic Risk Score (GRS) which can identify people who are at risk of developing coronary heart disease prematurely because of their genetics.

Genetic factors have long been known to be major contributors of someone’s risk of developing coronary heart disease – the leading cause of heart attacks. Currently to identify those at risk doctors use scores based on lifestyle and clinical conditions associated with coronary heart disease such as cholesterol level, blood pressure, diabetes and smoking. But these scores are imprecise, age-dependent and miss a large proportion of people who appear ‘healthy’, but will still develop the disease.

The ‘big-data’ GRS technique takes into account 1.7 million genetic variants in a person’s DNA to calculate their underlying genetic risk for coronary heart disease.

The team analysed genomic data of nearly half a million people from the UK Biobank research project aged between 40-69 years. This included over 22,000 people who had coronary heart disease.

The GRS was better at predicting someone’s risk of developing heart disease than each of the classic risk factors for coronary heart disease alone. The ability of the GRS to predict coronary heart disease was also largely independent of these known risk factors. This showed that the genes which increase the risk of coronary heart disease don’t simply work by elevating blood pressure or cholesterol, for example.

People with a genomic risk score in the top 20 per cent of the population were over four-times more likely to develop coronary heart disease than someone with a genomic risk score in the bottom 20 per cent.

In fact, men who appeared healthy by current NHS health check standards but had a high GRS were just as likely to develop coronary heart disease as someone with a low GRS and two conventional risk factors such as high cholesterol or high blood pressure.

These findings help to explain why people with healthy lifestyles and no conventional risk factors can still be struck by a devastating heart attack.

Crucially, the GRS can be measured at any age including childhood as your DNA does not change. This means that those at high risk can be identified much earlier than is possible through current methods and can be targeted for prevention with lifestyle changes and, where necessary, medicines. The GRS is also a one-time test and with the cost of genotyping to calculate the GRS now less than £40 GBP it is within the capability of many health services to provide.

Senior author Professor Sir Nilesh Samani, Professor of Cardiology at the University of Leicester and Medical Director at the British Heart Foundation said: “At the moment we assess people for their risk of coronary heart disease in their 40’s through NHS health checks. But we know this is imprecise and also that coronary heart disease starts much earlier, several decades before symptoms develop. Therefore if we are going to do true prevention, we need to identify those at increased risk much earlier.

“This study shows that the GRS can now identify such individuals. Applying it could provide a most cost effective way of preventing the enormous burden of coronary heart disease, by helping doctors select patients who would most benefit from interventions and avoiding unnecessary screening and treatments for those unlikely to benefit.”

Lead author Dr Michael Inouye, of the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute and University of Cambridge said: “The completion of the first human genome was only 15 years ago. Today, the combination of data science and massive-scale genomic cohorts has now greatly expanded the potential of healthcare.

“While genetics is not destiny for coronary heart disease, advances in genomic prediction have brought the long history of heart disease risk screening to a critical juncture, where we may now be able to predict, plan for, and possibly avoid a disease with substantial morbidity and mortality.”

This study was supported by funding from the British Heart Foundation, National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC, Australia), the Victorian Government and the Australian Heart Foundation and the NIHR. It was published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

NIHR researcher nominated for The Sun’s Who Cares Wins health awards

NIHR-funded researcher Professor Roman Hovorka has been nominated for the Groundbreaking Pioneer or Discovery category of The Sun’s Who Cares Wins health awards for his research developing an artificial pancreas for people with type 1 diabetes.

The Who Cares Wins health awards were launched in memory of the late Sun Health Editor Christina Earle to recognise the selfless medics, researchers and volunteers who work in the NHS. Now in their second year, the awards are this time also marking the 70th anniversary of the NHS.

Prof Hovorka and his colleagues at the NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre have developed an artificial pancreas hooked up to a smartphone that has the potential to transform management of type 1 diabetes.

Artificial pancreas device

Type 1 diabetes is one of the most common chronic diseases, affecting more than 400,000 people in the UK. People with type 1 diabetes are dependent on insulin injections several times a day to control their blood sugar levels – around 65,000 injections over their lifetime. This regular delivery of insulin is critical to reduce the risk of dangerous fluctuations in blood sugar levels, which can lead to serious complications such as eye, heart and kidney disease.

The artificial pancreas, which was highlighted as one of the 70 discoveries that have transformed NHS in NIHR’s I Am Research campaign, combines a continuous glucose monitor, insulin pump and smartphone. The device monitors blood sugar levels 24/7 to calculate and deliver the correct amount of insulin needed at any particular time. This approach cuts out the need for injections, improves blood sugar control, and reduces the likelihood of risky peaks and troughs in blood sugar levels.

A prototype of the artificial pancreas that Prof Hovorka has developed is currently being trialled in a study funded by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme. The research, taking place across six centres in the UK including the NIHR Cambridge Clinical Research Facility, is recruiting 100 young patients aged 10-16 with type 1 diabetes (the CLOuD Study).

Early results from the trial indicate that the artificial pancreas significantly improves blood sugar control overnight, helping patients to sleep better and perform better during the day. Should the final study results prove positive and the artificial pancreas be adopted into standard care, it will revolutionise treatment for patients with type 1 diabetes.

Prof Hovorka’s artificial pancreas research was one of three entries shortlisted out of thousands for the Groundbreaking Pioneer or Discovery category of The Sun’s awards. Prof Hovorka said: “I am thrilled that our research limits the highs and lows of blood glucose levels in people with type 1 diabetes, allows parents to sleep throughout night and makes life more enjoyable for all involved. I am honoured to have been nominated for the work I and my deeply dedicated team have done.”

The UK’s leading mental health experts unite to solve treatment challenges

The country’s top mental health researchers and clinicians are joining forces to solve some of the greatest mental health challenges facing the UK public.

The group of investigators, based in leading universities and hospitals across the country, will form a new NIHR Mental Health Translational Research Collaboration (TRC) which will work with industry and charity partners to find new treatments and therapeutics.

Currently, it is estimated that one in four people in the UK is living with a mental health condition. That’s nearly 15 million people with an illness that affects their wellbeing, their relationships with family and friends, and their ability to work.

The new NIHR Mental Health TRC will carry out much-needed scientific research to help transform the lives of those affected by mental illness. The initial focus of the collaboration will be on trying to better understand treatment resistant depression and improving characterisation of those individuals deemed to be ‘at risk’ of developing mental illness. It will also develop well-defined patient cohorts who have consented to be recalled to future mental health research studies in order to increase the numbers of people with mental disorders taking part in experimental medicine studies and trials.

The NIHR Mental Health TRC will follow a similar operating model to that already established through the NIHR’s collaborations in joint and related inflammatory diseases, respiratory disease and dementia.

The NIHR Mental Health TRC is underpinned by world class clinical research facilities provided by the NIHR’s Biomedical Research Centres and Clinical Research Facilities, and the NIHR Mental Health MedTech Co-operative, but it acts as a single partnership. This means that research opportunities can be explored more easily and quickly and provides a single point of contact for partners such as industry and medical research charities to work with the 11 participating centres of excellence. It also speeds up the negotiation of agreements and contracts and coordinates all steps from first contact through to delivery of the agreed project and ultimately the development of new interventions, technologies and diagnostics.

Dr Louise Wood, Director of Science, Research and Evidence at the Department of Health and Social Care, said: “Mental ill-health is the largest single cause of a disability in the UK and is a significant burden on people’s lives and on society. If we are going to improve people’s chances of living well and being able to work, we need to speed up the development of new treatments, particularly for those for whom current therapies do not work. The NIHR Mental Health TRC is bringing together the expertise of some of the best researchers in universities, the NHS, charities and industry to do just that. It will play a key part in the development pathway for potential new treatments, hopefully bringing them to people living with mental health conditions faster.”

Professor Matthew Hotopf CBE, Director of the NIHR Maudsley Biomedical Research Centre and Chair of NIHR Translational Research Collaboration in mental health said: “There are enormous opportunities for innovation as science and technologies relevant to mental disorders are increasingly producing results, particularly in neurosciences and digital technologies. By working collaboratively, we can accelerate this innovation to help those with mental illness.”

MQ: Transforming Mental Health is the TRC’s charity partner and will be part of the steering group as well as providing financial support to assist with the running of the collaboration.

Dr Sophie Dix, Director of Research at MQ: Transforming Mental Health said: “We’re delighted to support this important initiative which further catalyses the UK’s world-leading role in mental health research. Importantly, it will significantly increase the scale and reach of innovative research so we can bring forward much-needed advances in our understanding and treatment of mental illness.

EDGE user training for CUH research staff

In March 2017, an announcement was made by the NIHR that instructed each Clinical Research Network (CRN) to obtain a Local Portfolio Management System on behalf of their partner organisations. The system chosen for use at Cambridge University Hospitals (CUH) by CRN Eastern was EDGE. EDGE captures the clinical trials data and supports the delivery and maintenance of research at CUH.

Since then, information was sent out to research staff to make sure they had nominated administrators to be trained and start recording study recruitment data on the system. Over 230 users have been trained how to use the cloud-based software platform and staff are now using this system to register their activity for portfolio studies at CUH and upload their accruals on time.

EDGE is not a replacement for the Central Portfolio Management System (CPMS) but it does integrate into CPMS. EDGE will cover recruitment for CUH as a site but only for portfolio studies. Staff will still need to add recruitment data to CPMS for studies where CUH is the lead.

How to know if you need to receive the training?

- Do you have access to EPIC?

- Are you in a research team?

- Are you involved in an active portfolio research study?

- Will you be responsible to upload recruitment for CUH?

If you have answered “YES” to all of these questions, you will need to attend the EDGE End User Training sessions. Choose the date below you would like attend and complete the form.

Places are allocated on a first-come, first-serve basis. For more information on either training course, email CUH EDGE Team.

Finding meaningful patterns in the complexity of ovarian cancer

Patterns of genetic mutation in ovarian cancer are helping make sense of the disease and could be used to personalise treatment in future, according to a study published in Nature Genetics.

Researchers from the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, University of Cambridge and Imperial College London have found distinct patterns of DNA rearrangement that are linked to patient outcomes.

High grade serous ovarian cancer, the most common type of ovarian cancer, is referred to as a ‘silent killer’ because early symptoms can be difficult to pick up. By the time the cancer is diagnosed, it is often at an advanced stage, and survival rates have not changed much over the last 20 years.

But late diagnosis isn’t the only problem. Ovarian cancer genomes are particularly chaotic – they contain a scrambled mess of genetic code that has been chopped up, flipped over, incorrectly copied or deleted, or repeatedly copied over and over again. This makes it extremely difficult to understand what has caused a patient’s cancer and how that patient will respond to treatment.

In this study of ovarian cancer samples from over 500 women, the research team harnessed big data processing techniques to look for broad patterns in the genetic readouts from ovarian cancer cells.

Rather than focusing on the detail of each individual mistake in the DNA, they designed powerful computer algorithms to scan the genetic data, finding seven distinct patterns.

They showed that each pattern, or “signature”, represented a different mechanism of DNA mutation. Taken together, these signatures were able to make sense of the chaos seen in ovarian cancer genomes.

Surprisingly, all patients studied showed more than one signature, suggesting that multiple mechanisms change ovarian cancer cells during the life of these cancers. This might explain why the disease is so hard to beat with therapies target just a single mechanism.

The signatures were also linked to how well the patients responded to different treatments and whether they were likely to become resistant to chemotherapy. Two of the signatures predicted particularly poor survival outcomes, and two signatures identified patients with good outcomes.

Dr James Brenton, co-lead researcher, based at the Cancer Research UK Cambridge Institute, said: “Choosing personalised therapies for women with high grade serous ovarian cancer is difficult because of the very complex genetic changes in their cancer cells. Our study is a turning point for our understanding of the disease as for the first time we can see each patient’s unique combination of mutation patterns and start to identify the genetic causes of a patient’s cancer using cheap DNA testing in the clinic. The next step will be to develop methods to work out how to target these genetic causes with new therapies in trials.”

The researchers are now planning a clinical trial on ovarian cancer patients to see whether the seven signatures help doctors choose the best treatment for patients.

Professor Iain McNeish, co-lead researcher and Director of the Ovarian Cancer Action Research Centre at Imperial College London, said: “Ovarian cancer lags behind many other cancers because we haven’t been able to understand how its complex molecular changes relate to targeted therapies. Our new approach helps to decode the complexity and will improve outcomes and treatment choices for our patients.”

Cary Wakefield, Chief Executive of research charity Ovarian Cancer Action, said: “BriTROC was a unique project to co-fund as it brought together over 280 patients from 15 hospitals across the UK. This is a very exciting breakthrough in understanding this complex disease which in turn will facilitate better treatment options. Together we are all working towards a shared goal – where no woman dies of ovarian cancer.”

This research was funded by Ovarian Cancer Action, Cancer Research UK, and National Institute for Health Research Cambridge and Imperial Biomedical Research Centres.

*Reference: Macintyre et al Copy number signatures and mutational processes in ovarian carcinoma Nature Genetics

Written by Cambridge CRUK Institute

New research shows most women unlikely to benefit from national AAA screening

New research published in the Lancet and funded and supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has come to important conclusions about screening women for abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs).

The NHS introduced ultrasound screening in men aged 65 and over in 2009 to detect and treat the condition – which arises when the main blood vessel swells in the abdomen, and is symptomless until the point of rupture. Since the launch, the programme has been successfully screening and identifying men at risk of an AAA.

Researchers wanted to see if UK women – who are less likely to have AAAs – could also benefit from a similar screening programme.

Co-author Professor Matthew Bown, from the University of Leicester and honorary consultant vascular surgeon at Leicester’s Hospitals, said: “AAA is a serious condition and although it is less common in women we investigated whether extending the screening to women would be beneficial.”

Project leader and Cambridge statistician Professor Simon Thompson said: “In this project we used a sophisticated computer model to find out whether an AAA screening programme for women would be cost-effective.

“This showed that if women were also offered screening, only a very small number would benefit and the cost of such a screening programme would not be a good use of NHS resources.”

But more research is needed to understand this condition in women. Study co-author Janet Powell, Visiting Professor at Imperial College, said: “We need better information on aortic sizes of women at different ages, and whether screening has adverse effects on quality of life.

“A future step would be to see if there are certain groups of women at higher risk of the disease who might benefit from a targeted screening programme.”

- The SWAN study team included researchers from the University of Cambridge, Imperial College London, the University of Leicester, the University of Sheffield and Brunel University London. For more information about the project

- For more information about the NHS AAA screening programme

- For more information about the AAA at Cambridge University Hospitals

- Read the full paper

Baby’s sex affects the mother’s metabolism and may influence the risk of pregnancy-related complications

The sex of a baby controls the level of small molecules known as metabolites in the pregnant mother’s blood, which may explain why risks of some diseases in pregnancy vary depending whether the mother is carrying a boy and girl, according to new research from the University of Cambridge.

The findings, published today in JCI Insight, help to explain for example, why male babies in the womb may be more vulnerable to the effects of poor growth, and why being pregnant with a girl may lead to an increased risk of severe pre-eclampsia for the mother.

A team led by researchers at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre, performed detailed scientific studies of more than 4,000 first time mothers and analysed samples of placenta and maternal blood.

They found that the genetic profile of the placentas of male and female babies were very different in relation to the baby’s sex. Many of the genes that differed according to the sex of the baby in  the placenta had not previously been seen to differ by sex in other tissues of the body.

the placenta had not previously been seen to differ by sex in other tissues of the body.

The team found that one of these uniquely sex-related placental genes controlled the level of a small molecule called spermine. Spermine is a metabolite – a substance involved in metabolism – that plays an important role in all cells and is even essential for the growth of some bacteria.

Female placentas had much higher levels of the enzyme that makes spermine, and mothers pregnant with baby girls had higher levels of a form of spermine in their blood compared to mothers pregnant with baby boys.

Placental cells from boys were also found to be more susceptible to the toxic effects of a drug that blocked spermine production. This provided direct experimental evidence for sex-related differences in the placental metabolism of spermine.

The researchers also found that the form of spermine which was higher in mothers pregnant with a girl was also predictive of the risk of pregnancy complications: high levels were associated with an increased risk of pre-eclampsia (where the mother develops high blood pressure and kidney disease), whereas low levels were associated with an increased risk of poor fetal growth.

The patterns observed were all consistent with previous work which has shown that boys may be more vulnerable to the effects of fetal growth restriction and being pregnant with a girl may lead to an increased risk of severe preeclampsia.

“The work provides a possible mechanism for a long standing theory in evolutionary biology which suggest that girls may be better equipped to survive poor nutrition in the womb than boys,” says Professor Gordon Smith from the University of Cambridge, who led the study. “It may also lead to better understanding of how nutrition in pregnancy might be related to the risk of complications.”

The work was supported by NIHR Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and the Medical Research Council.

Written by the University of Cambridge

Second stage of EDGE training for research staff

Since the launch of EDGE in 2017, 230 users have been trained how to use the cloud-based software platform. EDGE system captures the clinical trials data and supports the delivery and maintenance of research at CUH. Staff are now using this system to register their activity for portfolio studies at CUH and upload their accruals on time.

CUH EDGE team will be launching a further stage of EDGE training called End User Advanced training – this is for staff that would like to know more functionalities of the system for their day-to-day work when capturing clinical trials data.

This next stage of End User Advanced training will be offered in September 2018, and to attend you must have already completed the End User training. Click on the link below to register, you will be added to the list and will be sent further information in due course.

Book your place here or for further information contact our EDGE team.

Dr Amos Burke wins Windrush70 award

Congratulations to one of our researchers and consultant paediatric oncologist Dr Amos Burke, who won the research and policy development award at the NHS Windrush70 awards on the 12th June.

Seven members of staff from Cambridge University Hospitals (CUH) were nominated for these awards, celebrating the contributions of black and minority ethnic (BME) staff across the NHS workforce.

Dr Burke joined CUH in 2004, and combines clinical practice with significant research in children studies. Read Amos’ winning nomination here.

Cambridge researchers put on a blooming good show

Cambridge researchers studying the HIV virus have helped create a garden at this year’s Chelsea Flower Show to highlight the plight of young people living with the condition.

Cambridge-based Professor Andrew Lever is part of the CHERUB network of researchers from NIHR Biomedical Research Centres in Cambridge, London and Oxford who are searching for a cure for HIV.

Current treatments suppress the virus very effectively and people remain well but eradication is not yet possible so treatment has to be lifelong.

The CHERUB collaboration was formed to investigate new ways to try and cure HIV and has recently concluded a large clinical trial of a novel approach to try and eradicate HIV from those who are infected.

The garden, representing both CHERUB and CHIVA (Children’s HIV Association), A Life Without Walls, was the brainchild of Professor John Frater from Oxford University and Professor Sarah Fidler from Imperial College London, and designed by Naomi Ferrett-Cohen.

Prof Lever said: “The garden symbolises the obstacles and darkness that young people living with HIV have to face but it’s also full of hope – the end of the journey leads you to a bright space where the walls have been broken down.

Actor Alison Steadman and gardener and broadcaster Monty Don in the CHERUB garden A Life Without Walls.

“This represents a society where these young people are accepted without prejudice and feel happy and confident to open up about their HIV, without fear of judgement.”

HIV is now treatable but young people living with the condition may have suffered multiple bereavements and/or taken on caring responsibilities. On top of this they must manage growing up with a highly stigmatised chronic illness.

Prof Lever said: “The garden represents the breaking down of this stigma and intends to show that anyone can live well and openly with HIV.”

The garden also has another message – that everyone needs to work hard to find a cure through dedicated scientific research.

The RHS Chelsea Flower Show takes place at the Royal Chelsea Hospital from 22-26 May. For more information about the work of CHERUB see cherub.uk.net or follow CHERUB on Twitter: @ukcherub or see pictures of the garden.

Top right photo shows CHERUB researchers Prof Andrew Lever (left) from Cambridge and Prof John Frater from Oxford.

Six months of Herceptin could be as effective as 12 months for some women with HER2 positive breast cancer

For women with HER2 positive early-stage breast cancer taking Herceptin for six months could be as effective as 12 months in preventing relapse and death, and can reduce side effects, finds new research.

The PERSEPHONE trial, a £2.6 million study funded by the NIHR with translational research funded by Cancer Research UK, recruited over 4,000 women and compared a six month course of treatment of Herceptin with the current standard of 12 months for women with HER2-positive early-stage breast cancer. This is the largest trial of its kind examining the impact of shortening the duration of Herceptin treatment.

Herceptin, has been a major breakthrough, prolonging and saving the lives of women with breast cancers that carry the HER2 receptor on the surface of their cancer cells. Around 15 out of every 100 women with early breast cancers have HER2 positive disease. Herceptin is a targeted therapy that works by attaching to the HER2 receptors preventing the cancer cells from growing and dividing. It has rapidly become standard of care and based on clinical research a 12 month treatment course was adopted. However, a further clinical study suggested a shorter duration could be as effective, significantly reducing side effects and cost both to patients and to the NHS.

The trial, led by a team from the University of Cambridge and Warwick Clinical Trials, the University of Warwick, found that 89.4% of patients taking six months treatment were free of disease after four years compared with 89.8% of patients taking treatment for 12 months. These results show that taking Herceptin for six months is as effective as 12 months for many women. In addition, only 4% of women in the six month arm stopped taking the drug early because of heart problems, compared with 8% in the 12 month arm. Women also received chemotherapy (anthracycline-based, taxane-based or a combination of both) while enrolled in the trial.

Professor Helena Earl

Lead study author Professor Helena Earl, Professor of Clinical Cancer Medicine, University of Cambridge, Cancer Research UK Cambridge Centre and Cambridge BRC researcher, said “The PERSEPHONE trials team, patient advocates who have worked with us on the study and our investigators are very excited by these results. We are confident that this will mark the first steps towards a reduction of Herceptin treatment to six months in many women with HER2-positive breast cancer. However, any proposed reduction in effective cancer treatment will always be complex and very challenging, and women currently taking the medication should not change their treatment without seeking advice from their doctor. There is more research to be done to define as precisely as possible the particular patients who could safely reduce their treatment duration. We are poised to do important translational research analysing blood and tissue samples collected within the trial to look for biomarkers to identify subgroups of different risk where shorter/longer durations might be tailored.”

Professor Hywel Williams, Director of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme that funded the PERSEPHONE study said: “This is a hugely important clinical trial that shows that more is not always better. Women will now have the potential to avoid unnecessary side effects of longer treatment without losing any benefit. In turn, this should help save vital funds for the NHS and prompt more studies in other situations where the optimum duration of treatment is not known. It is unlikely that research like this would ever be done by industry, so I am delighted that the NIHR are able to fund valuable research that has a direct impact on patients.”

Professor Charles Swanton, Cancer Research UK’s chief clinician, said: “This is a critically important study that the breast cancer field has been eagerly awaiting. Targeted therapies, while effective, come at a huge health economic cost to the NHS as well as potentially causing side effects such as heart problems. Despite years of research, we haven’t been able to establish the optimal duration of Herceptin treatment, either to delay cancer coming back or to cure patients with early HER2+ breast cancer following surgery.

“The exciting early key findings from this study show that 6 months of Herceptin might be as effective as 12 months, and it may also be safer and with fewer side effects. By analysing tumour and blood samples, the researchers will now try to understand which patients can stop Herceptin at 6 months and which patients need extended therapy.”

Maggie Wilcox, President of Independent Cancer patients Voice (ICPV) who is the patient lead for the PERSEPHONE trial, said “I am delighted to have been part of this landmark trial which is an important step to reduce the length of treatment whilst not changing effectiveness. Most trials add novel treatments to standard practice whilst this has set out to reduce duration of Herceptin. The collection of the patient reported experiences throughout the trial will greatly inform future practice and benefit patients. ICPV is working with the Persephone team to help disseminate these exciting results’.

The results of the trial, PERSEPHONE, will be presented at the upcoming 2018 ASCO Annual Meeting in Chicago. The full report, which will include analysis to determine the impact of treatment length on quality of life and a detailed cost effectiveness analysis, will publish in the NIHR journals library. Visit the project page for more information.

Patient and Public Involvement training for researchers

The NIHR Cambridge BRC is offering all research staff a training session on Patient and Public Involvement.

The half-day session will provide staff with an introduction to Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) such as the ‘what’ and ‘why’, and will outline through case studies what PPI methods might be suitable for a research study.

There will be information of how to conduct PPI projects and finding out about local support available to help staff plan and deliver their PPI.

Who can attend?

The event is free and open to all, but particularly aimed at staff who are new to PPI and will be setting up their first PPI project. Research staff do not have to be funded by the NIHR to attend this training session. There is a limited number of places available and booking is on a first-come, first-served basis.

Contact the PPI team for a list of the next available dates.